Native Plants for Textiles: 3 Bast Fibers to Know Beyond Hemp and Flax

Bast fibers have been highly regarded for beautiful, durable textiles throughout history and into the modern era. As part of our ongoing Bast Fiber Research effort, Fibershed engaged mechanical engineer Nicholas Wenner to connect with bast fiber growers, researchers, processors, and artisans to better understand the state of soil-to-soil systems for these unique plants. In the plant, bast fibers transport dissolved sugars and lend structural support for the stem. In textiles, the fibers provide strength and many other unique properties. As crops, the plants can play a valuable role in crop rotations and provide high yields of both food and fiber with relatively minimal inputs

Bast fibers have a long relationship with humans: the earliest known fibers used by humans include wild flax fibers from 34,000 years ago found in a cave in the country of Georgia. Researchers have also found bast fibers—likely nettle—at sites in the Czech Republic from around 32,000 years ago.

Hemp and flax are the most well-known bast fibers, followed perhaps by ramie, a nettle-like plant native to eastern Asia used for coarse fabrics and rope. Many other bast fiber plants have been used for textiles throughout history and the world.

In addition to working with hemp and flax last year (read more in our 2019 blogs), we collaborated with local farmers and indigenous land tenders to harvest and process three native bast fiber plants—dogbane, nettle, and milkweed—into fiber suitable for spinning into yarn. All three plants have value as perennial crops that grow well in local climates. With materials from each plant, we developed a Bast Fiber Exhibit for the 2019 Fibershed Gala and the 2019 Wool and Fine Fiber Symposium to provide both a tactile understanding of bast fiber processing and a hands-on comparison between fiber types. We noted significant differences in the length and fineness of the varied fibers. Hemp had the longest and coarsest fiber, while milkweed had exceptionally soft but short fiber. Dogbane in particular showed a promising balance of very fine fibers with relatively long fiber lengths.

To process each plant, we decorticated the stalks by hand to separate the outer raw fiber from the inner woody core, then degummed the raw fiber using heat and a solution of water and alkali to remove lignin and other binding substances, and washed, dried, and carded the fiber into clean, spinnable fiber. We paired specimens of each plant with samples of raw fiber, degummed fiber, hurd, seeds, and other products, such as edible leaves from nettle and flower buds from hemp.

Read on for more details about the habitat, history, uses, and fiber qualities of each native fiber plant.

Dogbane

Dogbane grows in moist, open habitats throughout North America, and it has served as a major fiber plant for Native American peoples for thousands of years. Europeans gave the Latin name Apocynum cannabinum to the plant because of the similarity between its fiber and that of hemp (Cannabis sativa). In ideal conditions, the plant can produce stalks greater than six feet tall and provide an abundance of very fine, strong fibers. Similar to flax, dogbane stalks have relatively few and relatively small leaf nodes, which supports the production of long, continuous fibers. These fibers require relatively little processing compared to hemp, and fibers fine enough for many purposes can be obtained directly from dried stalks without retting or degumming. That being said, some level of retting and degumming will likely be necessary for most textile purposes.

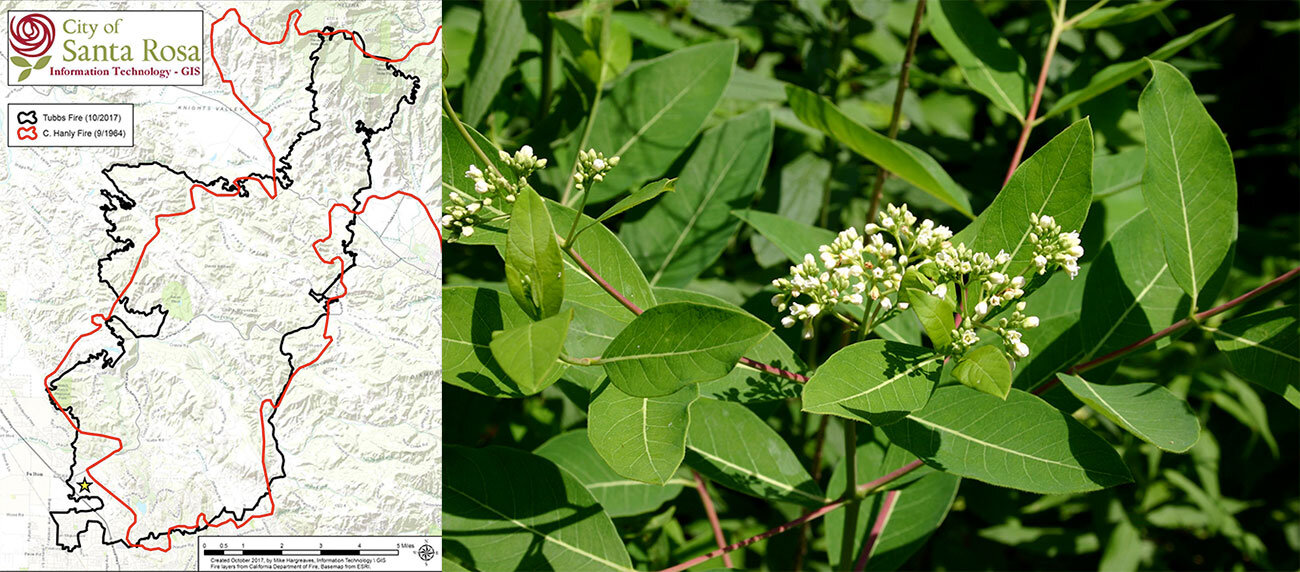

With permission and guidance from indigenous land tenders, we harvested dogbane for the Bast Fiber Exhibit from a patch in Sonoma County that has been continuously tended for thousands of years and is within the traditional and ancestral territory of Southern Pomo and Coast Miwok peoples. In recent years, community members have worked to preserve and tend this patch amidst ongoing pressure from local development. The site is now protected under the Sonoma County Agricultural Preservation and Open Space District, and volunteers tend the site throughout the year by clearing brush and weeds and otherwise maintaining habitat for the plant. The preserve hosts a day of cordage making and stewardship each winter, and you can read about a recent event here.

Dogbane plays culturally significant roles for local indigenous groups. For example, the Southern Pomo and Coast Miwok traditionally relied on the plant’s strong fibers for string, thread, rope, baskets, snares, netting, and clothing, and cordage from the plant was used to make straps, belts, netted bags, hairnets, and ceremonial regalia. The plant had many medicinal uses as well.

Fire was used historically as a tending strategy by indigenous people to clear brush and promote the growth of dogbane, but recent fire regulations and nearby developments have made it difficult to maintain this practice. In a rare silver lining to recent fires in the region, the patch burned in 2017 as part of the Tubbs Fire, and those tending the patch now report vigorous and healthy growth, partly due to the reduction of invasive Himalayan blackberry and Harding grass.

Dogbane fiber shows a good combination of fineness and length. Alongside milkweed, it was the finest of the fibers we processed, and dogbane fibers were similar in length to those of nettle. While shorter than fibers from flax and hemp, the dogbane fibers had sufficient length to be spun on cotton equipment.

Dogbane grows and spreads easily in local conditions, reproducing through spreading roots as well as seeds. In fact, many landscapers and home gardeners struggle with dogbane taking over the areas they tend, and in some agricultural contexts the plant is considered a weed and competes well enough to create significant yield losses in fields of soy, corn, and other crops.

Dogbane supports several species of moths and provides abundant nectar to pollinators. As a vigorous, perennial source of fine fiber and habitat, dogbane has much promise as a component in regional fiber systems.

Nettle

Nettle (Urtica dioica) grows perennially in moist soils throughout North America. Often known as “stinging nettle,” its leaves and stems are covered with small, thin, needle-like spines that can cause irritation if touched by bare skin. Once the plants have wilted, the spines are largely inert, and nettle leaves are commonly used as tea and eaten as food. Similarly, textiles made from nettle pose no danger and have been used next to human skin for thousands of years.

Seam Siren produces clothing from Himalayan nettle (Girardinia diversifolia) in partnership with Nepalese producers and shared perspectives on these efforts at the Fibershed 2017 Wool and Fine Fiber Symposium.

The nettle fiber we processed came from a subspecies of nettle known as hoary nettle (Urtica dioica ssp. holosericea). Compared to other local nettles such as California nettle (Urtica dioica ssp. gracilis), hoary nettle can grow very tall, commonly reaching above 8 feet. The sizes of the stalks and the fiber yields from each stalk are similar to those of some hemp. The fibers we processed were finer than those of hemp and similar to those of flax. In length, they were shorter than hemp and flax fibers and similar to those of dogbane.

In addition to fiber and food, nettle offers a green dye from the leaves and a yellow dye from the roots. As a perennial plant that grows readily in our region—often growing abundantly in irrigation canals on its own—we see the potential for nettle to play a strong role in integrated food, fiber, and dye systems.

Milkweed

Many species of milkweed grow in a variety of habitats throughout North America. They are classified in the genus Asclepias, which sits in the same family as dogbane. At least 19 species grow in California, including narrow-leaf milkweed (Asclepias fascicularis), which can be found in dry, open areas throughout the state, and showy milkweed (Asclepias speciosa), which grows in more mountainous, wetter areas. Milkweeds are named for an abundant, milky-white latex “sap” that seeps from injured portions of the plant. The latex contains chemical compounds the plants use to fend off predation from insects and other animals. Most milkweed plants are toxic for human consumption due to these defenses, although some milkweed species may be made edible if properly processed.

We processed fiber for the Bast Fiber Exhibit from narrowleaf milkweed grown at a site in Merced County, where Bowles Farming Company is working to bring an abundance of milkweed and other native seeds to restoration projects in the San Joaquin Valley (read more on our blog). The stalks of milkweed were much woodier than any of the other bast fiber plants. While the bast fibers were quite short—seldom reaching more than one inch long—they were extremely fine, similar to those of dogbane. Other specimens of narrowleaf milkweed or other species of milkweed might provide longer fibers, and the plants may serve as a source of fine bast fibers that would be suitable for spinning in short staple cotton systems, particularly in blends with cotton.

In addition to bast fiber, milkweed produces a cotton-like fiber from its seeds known as floss. While milkweed floss is too smooth to spin easily and does not form strong yarns on its own, the fiber is hollow and has been used commercially as a fill and insulation material for decades. The floss was used at an industrial scale during World War II as a fill for life jackets and it is currently processed and used on a small scale for winter jacket insulation.

Milkweed species also have benefits as habitat, providing strong nectar sources for pollinators and the sole habitat for caterpillars of the monarch butterfly. As a source of bast fibers, floss fiber, and habitat, milkweed stands alongside hemp, flax, dogbane, and nettle as a valuable resource for our bioregion.

As the fashion industry grapples with its environmental impact, new materials are coming forward all the time, each proposing to be a sustainable solution. Bast fiber plants have proven their value throughout tens of thousands of years of relationship with humans. Their cultivation can be rooted in modern agroecological methods and offers a way to meet material needs with beautiful, natural textiles with a range of properties from breathability to biodegradation. Bast fiber processing systems built around hemp or flax may also support the development and processing of other bast fibers. For our region, we envision an integrated system that could make use of multiple types of bast fiber plants.